State of Racial Disparities

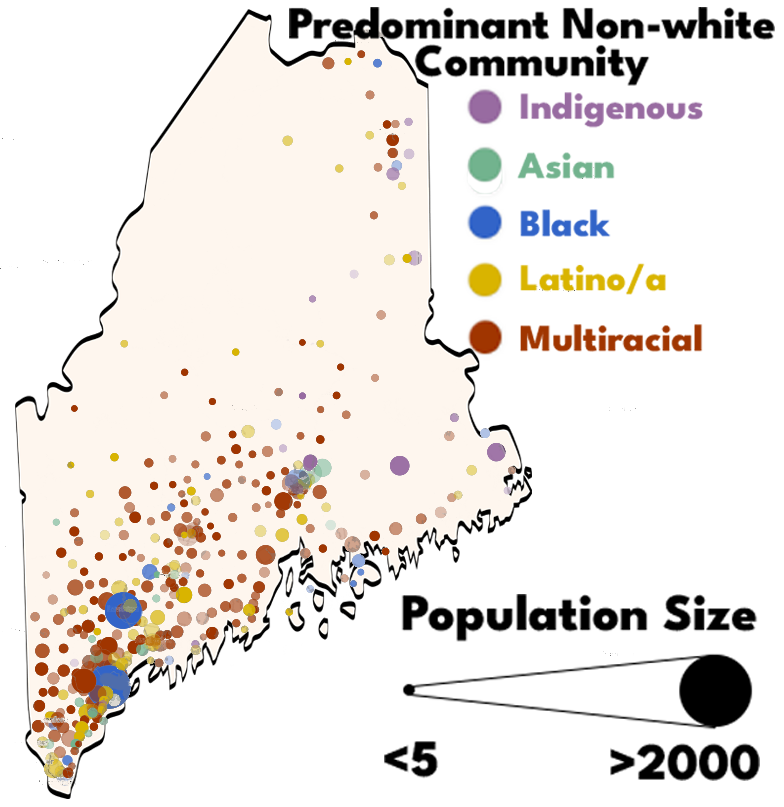

Maine, known for the rugged beauty of its forests, lakes, rivers, and coast, charming communities, and bountiful wildlife, holds a complex past. It’s also known as “the whitest state in America,” where many assume the history of racism and current racial inequality in the United States do not apply. This misperception overlooks the presence and vibrant cultural heritage of Wabanaki people and the significant contributions of Black Mainers since the early days of colonization. It also obscures a past that continues to impact people from all walks of life and areas of the state today.

Today, Maine ranks worst in the nation for racial disparities in homeownership. Mainers of color are up to nine times more likely than white Mainers to be incarcerated, and twice as likely to live below the poverty line. People of color in Maine are disproportionately and systematically underhoused, underpaid, and left without the resources they need to thrive in our public schools and places of employment. And our Wabanaki neighbors — the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq, and Maliseet — are unique among federally recognized tribes for not having the legal authority to self-govern, with far-reaching social and economic consequences. The factors that drive racial inequality harm all Mainers, regardless of race.

66%

As Mainers, we know that none of us can thrive while some of us are left behind. From housing to employment, healthcare to the criminal legal system, the impact of laws, policies, and practices that discriminate against people of color have left scars across our state that directly impact the lives of Mainers today.

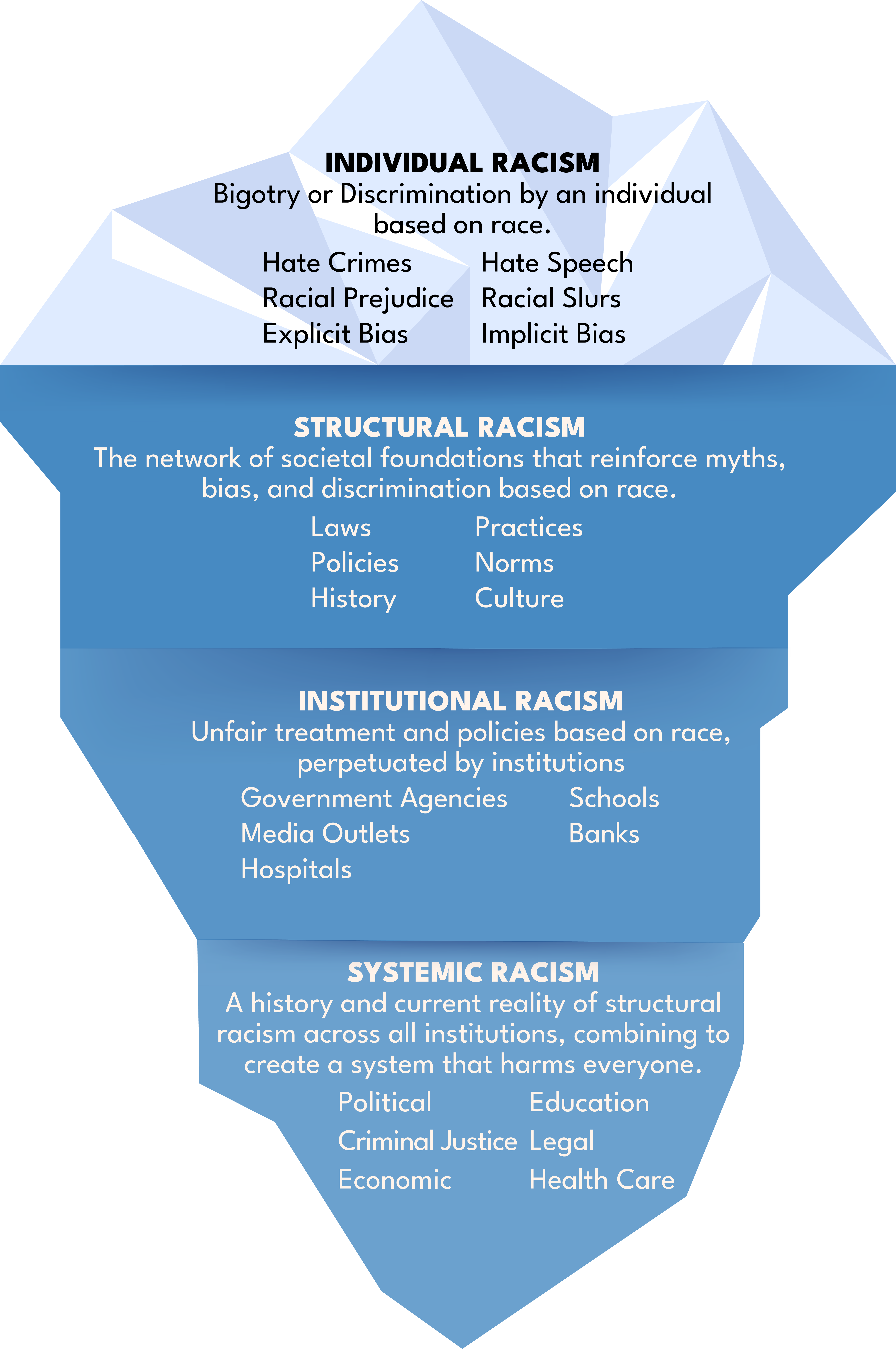

The Permanent Commission on the Status of Racial, Indigenous, and Tribal Populations is an independent government agency dedicated to understanding the disparities caused by historic injustice and working directly with impacted communities to build a brighter future where all Mainers can thrive. We conduct research, outreach, and community building, and advocate for policies that don’t just cover up the symptoms of racial injustice, but dismantle its root causes. This includes addressing institutional, structural, and systemic forms of racism that have emerged over time (see Figure 1).

|

Today, even as blatantly racist laws have been removed from the books, the ideas and assumptions that formed them are encoded into our language, culture, customs, and organizational structures. These systems were built throughout history with intention — and it will take intention to dismantle them.

As an important step in this effort, the Permanent Commission has identified key policy areas with known racial disparities. In each area, we scan the most recent literature, datasets, reports, and research to understand the pathways from which inequalities emerged and through which we can create lasting change. Findings in the following sections only brush the surface; we also provide resources so those who are interested can deepen their knowledge. This report and associated resources will be updated biennially to ensure that disparities in our state are named, tracked, and recognized in the light of day — not swept under the rug.

|

For clarity, this report breaks down racial inequalities in Maine into topical areas. We recognize these issues are inseparable — intertwined through histories of colonialism, enslavement, segregation, oppression, and erasure across scales from individual to institutional. Where meaningful, we also highlight how race intersects with gender, wealth, geography, and age, and we cross-reference sections to show how systemic harms connect and how policy changes can have broad impacts.

Perhaps most importantly, we acknowledge that the solutions to systemic racism exist not within but at the intersection of these areas — and always with communities at the center. Except where impacted communities have made their policy preferences clear, this report does not make specific policy recommendations. Instead, we hope these sections open doors for richer discussions with impacted communities about how to move forward together.

| NOTES |

|---|

|

1. Gotoff et al. (2024). Public Awareness and Perceptions of Disparities in Maine. Statewide poll indicating 66% of Mainers see inequality as a problem and a majority name racism as part of that problem. Methodology: phone survey of 850 Mainers, weighted to 2020 Census. |

|

2. Government Alliance on Race & Equity (2018). GARE Communications Guide. Definitions informing Figure 1. |

|

3. Braveman, P., Arkin, E., Proctor, D., Kauh, T. & Holm, N. (2022). Systemic And Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health Damages, And Approaches To Dismantling. Health Affairs. |