Place Justice in Maine

The Place Justice Project invites all who call Maine home to begin taking active notice of whose memory is visible and celebrated around us and whose has been erased or misrepresented. The Permanent Commission envisions a Maine that is safe and welcoming for all people and where all people, the land, and the water are cared for and protected based on their inherent dignity and worth.

Throughout the course of 2024, the Permanent Commission will update this section of the website with information, tools, and resources, including interactive maps related to geographic place names.

-

What is the Place Justice Project?

-

What is the Place Justice Project?

The Place Justice Project originated from a series of Resolves passed by the Maine State Legislature, most recently PL 2022, Ch 149 which directed the Permanent Commission to review state law regarding offensive place names.

The Permanent Commission expanded the scope of the project to consider more than “offensive names” as defined in Maine statute. Currently, Maine statute defines “offensive name” as the “n-word,” “sq-word,” or any derivative of these two words.

We sought to understand how geographic features are named in Maine, along with who is represented (and how) and who is absent in the names inscribed on land and waters.

The Place Justice Project has, over the course of 2022 and 2023, involved:

- Examining practices to name and rename geographic features

- Identifying the continued presence of “offensive names” as defined in statute, along with other places names that may negatively impact a sense of belonging.

- Engaging local communities and inviting dialogue about the history and meaning of place names.

- Holding listening sessions with impacted groups, and hosting public education events.

-

Why do place names matter?

-

Why do place names matter?

Place names are part of a commemorative landscape, designed by people, to tell specific stories about important moments, individuals, or markers of our past. Place names matter because they encode memories onto the landscape, telling stories about how we have lived, and by extension, about how we should live together. Because these familiar fixtures surround us all the time, they often go unnoticed. Even when we do not notice them — in fact specifically because we do not notice them — these names inform our sense of place in subtle ways, communicating ideas about who belongs and what is worthy of remembering.

Long before European settlers ever drew a map of this place and called it Maine, the vast homeland of the tribes comprising the Wabanaki Confederacy, including the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot knew this place as Ckuwaponahkik, or Dawnland: the place where the sun first looks our way. The violent removal of these people from the land is mirrored today in the language that adorns our maps and state symbology, erasing the story of Maine’s involvement in the colonial project. Likewise, our place names continue to reinforce the old mantra that Maine is the “whitest state in the nation,” taking such an assertion as a natural state of things, rather than a result of historical processes of erasure. As we consider what it means to embed justice into the fabric and function of our state, we find ourselves asking:

How did such violence come to be marked on the landscape and what can we do, as a collective community of people who love this place, to ensure that our towns, landmarks, and spaces of public gathering are welcoming to all who call this place home?

As noted by the federal Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names in its guiding visions and principles:

“Place name reconciliation works to align the nation’s place name landscape with the nation’s ongoing progress toward the values of truth and justice. The emphasis of place name reconciliation is reform. It is not about erasing names and histories from the American landscape, but correcting the use of derogatory place names and addressing the harm they inflict upon discriminated groups along with how they damage wider possibilities for cohesive social relations in the nation.”

-

What are offensive and derogatory place names?

-

Offensive Place Names

Maine (1 MRSA §1101) defines “place” as “any natural geographic feature or any street, alley or other road within the jurisdiction of the State, or any political subdivision of the State.” It defines “offensive name” as the “n-word,” “sq-word,” or any derivative of these two words.

Maine was ahead of the curve in addressing the issue of offensive place names. In 1977, the state’s first African American state legislator, Representative Gerald E. Talbot, sponsored an “An Act to Prohibit the Use of Offensive Names for Geographic Features and Other Places Within the State of Maine.” When Representative Talbot’s bill was signed into law, the event made national headlines.

In 2000, Passamaquoddy Tribal Representative Donald Soctomah sponsored “An Act Concerning Offensive Place Names,” which expanded the definition “offensive name” in Maine statute to include both the “n-word” and the “sq-word,” a term that has historically been used as a racist and sexist slur against Indigenous women.

However, 43 years after her father’s landmark bill was signed into law, in 2020 Representative Rachel Talbot Ross learned that it had not been effectively enforced. At that time, five Maine islands continued to bear offensive names - although Maine statute prohibited the use of “offensive names” for places in Maine, there had not yet been any process to rename places with these names. Officials hastened to change the names of three of the islands in question and instructed two other localities to follow suit. Representative Talbot Ross’ bill to determine if other offensive and problematic terms remain inscribed on Maine’s landscapes and maps was the origin of the Place Justice project.

Derogatory Place Names

In November 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland signed Secretary's Order No. 3405 (Addressing Derogatory Place Names), which directed the National Park Service to Establish a new Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names (ACRPN). The ACRPN’s November 2023 working definition of “derogatory place names” are terms attached to the national landscape and geographic features that:

- Are used or intended as a disrespectful, belittling, hurtful, or disparaging slur.

- Pejoratively labels any racial or ethnic group, gender, religious affiliation, sexual identity, or physical or mental condition.

- Uses insulting slang/linguistic derivatives to negatively stereotype certain social groups or identities.

-

Decisions taken at the federal level related to naming and renaming of geographic features also impact place names in Maine - relevant impacts are noted in the map below.

-

Who is represented in Maine place names?

-

Who is represented in Maine place names?

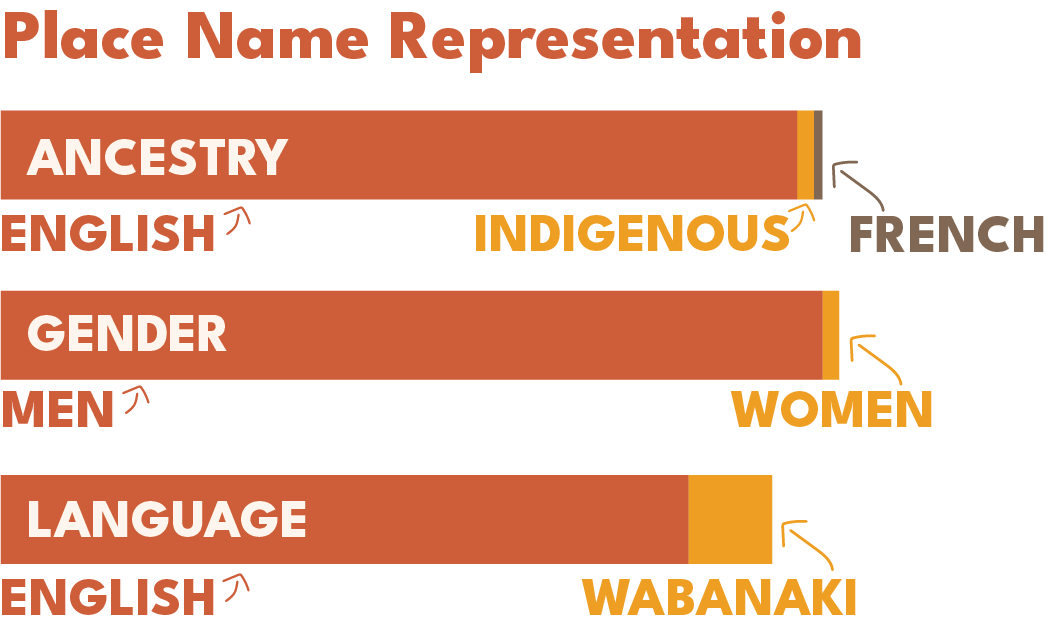

On reviewing over 18,000 place names in Maine, our team found:

Of the places named after individual people (8,626):- 95% (8,179) were named after people of English descent.

- 2% were named after Indigenous people.

- 1% named after people of French and Acadian ancestry.

- 98% (8,478) were named after or referred to men (often as landowners).

- 2% were named after or referred to women.

- 82% use English words.

- 10% are from Abenaki / Wabanaki languages.

-

Mapping Maine’s Place Names

-

Mapping Maine’s Place Names

The first step involves having a clear picture of Maine’s current and historical landscape. While the information we could uncover about each place and its history is in many ways limited, we believe presenting it as-is opens the door for communities to continue investigating and reflecting on the meaning, origins, and potential impacts of the places they live. The map below documents the place names across Maine that fit into one of four categories (as of January 2024):

Racial or ethnic slurs: words commonly understood to be racial or ethnic slurs (eg “Coon,” “Papoose,” “Redman”). The notes section for each entry includes brief details on how and why the words or phrases have been identified as slurs, whether it is due to a federal designation as derogatory, a common dictionary definition as a slur, or whether additional contextual research is needed.

Contains controversial language: Includes words that are controversial within the communities they refer to (specifically, “Negro” and “Indian”). Some communities and individuals consider these terms outdated and offensive and have called for their removal from place names across the country, while other individuals and communities see these as a way to recognize historic inhabitants. In most cases, additional local research may be beneficial to understand the context in which the name was given to the place.

Indigenous or African American references: Includes references to specific Indigenous or African American individuals. Preliminary research suggests that some places named after Indigenous people mark where they died rather than where they lived, and that some places named after people of African descent use Anglicized and/or ironic first names rather than the more respectful surnames often marking places commemorating prominent white individuals. In most cases, additional local research may be beneficial to understand the context in which the name was given to the place.

“Offensive names” changed by statute: Places that historically had names deemed “offensive” within Maine statute that have since been changed as required by law (i.e. previous appearances of the “n-word” or the “sq-word”). While these names are no longer legally recognized, in many cases, the previous name is still found on maps, town records, or other publicly available documents or mapping systems.

We will continue to add additional categories during the course of 2024.

The Permanent Commission is not sharing the map below for the purpose of making recommendations that any names be changed. Instead, we are sharing information for communities to learn more about their histories and, through partnership with those impacted by the names, to determine the best path forward.

We invite you to explore the map below and to consider whether there are geographic features near you with names that might not align with your community’s values.

PLEASE NOTE: This map contains words that are racist, harmful, derogatory, problematic, and considered offensive by many. We believe in the importance of an honest telling of history, and have chosen to include these terms either as they appeared on historical maps or as they continue to appear on maps today. Please use care when engaging with this resource.

Open the Map Methodology

In order to examine Maine place names, our team first considered all named geographic features in the state that are recognized by the United States Board on Geographic Names (USBGN)’s Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). After removing duplicates, the remaining 18,717 records were then merged with descriptive information from Phillip B. Rutherford’s Dictionary of Maine Place Names (1970), a work that synthesizes information from multiple sources about the origin of place names. Additional details on place name origins were collected from Gerald E. Talbot and Harriet H. Price’s Maine’s Visible Black History: The first chronicle of its people (MVBH) and through analysis of historical records, archives, and expert interviews. All records were reviewed and categorized. Each map entry contains information on a site’s current and historical names, its geographic location, and any available research on the origins of the name or history of name change over time.

-

How can I learn more?

-

How can I learn more?

Simply knowing that place names have complicated histories is not enough. Through our research, we have found that the presence of these names on the landscape can be potentially damaging — both to racial, Indigenous, and tribal populations, and to the cohesion of the communities where such names exist.

It is also these communities - in partnership with impacted populations and with the proper tools and resources in hand - who are also best situated to decide how to move place justice forward.

- View recordings of the seven-part Place Justice Event Series that took place during 2023.

- Connect with your local library or historical society to learn more about the history of the place you live.

- Check out The Wilderness Society’s publication “A guide to changing racist and offensive names in the United States” published in 2022.

- Consider how memory spaces can contribute to the prevention of identity-based violence, in “Beyond Remebering: An Atrocity Prevention Toolkit for Memory Spaces” published by the Auschwitcz Institute for the Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities.

- Explore the US Geographic Names Information System domestic names map and the federal Reconciliation in Place Names Committee.

- Learn more about how patterns around place naming emerge and are replicated across space and connect with your local historical society to learn more about the history of the place you live today.

- Track the progress of LD 1667 “An Act Regarding Recommendations for Changing Places Names in the State”, a proposal to create a diverse and inclusive Maine Board on Place Names, and read press coverage of the bill.

- Explore ways that you can support efforts within Maine to improve land access for Wabanaki and Black Mainers (and read our report on Black and Indigenous Land Access to know why this matters).

- Sign up for the Permanent Commission’s email newsletter to stay up to date as additional materials are released.

-

Acknowledgements

-

Acknowledgements

The Permanent Commission extends its sincere thanks to those who have contributed to the Place Justice Project.

Place Justice Advisory Council Members

Samaa Abdurraqib, Executive Director of Maine Humanities Council

Libby Bischof, USM Professor of History and Executive Director at Osher Map Library

Zeke Crofton-Macdonald, Ambassador for the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians

Maulian Bryant, PCRITP Co-Chair, Penobscot Tribal Ambassador

Stephen M. Dickson, Maine State Geologist, Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry

Bob Greene, Scholar of Maine’s Black history

Fiona Hopper, Wabanaki and Africana Studies lead at Portland Public Schools

Mishy Lesser, Director of the Upstander Project

Kate McBrien, Maine State Archivist

Kate McMahon, Scholar at Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture, Center for the Study of Global Slavery

Marcelle Medford, PCRITP Commissioner, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Bates College

Darrell Newell, former PCRITP Commissioner representing the Passamaquoddy Tribe

Darren Ranco, Chair of Native American Programs and Professor of Anthropology, University of Maine

Richard Silliboy, PCRITP Commissioner representing the Micmac Tribal Nation

Rachel Talbot Ross, PCRITP Co-Chair, Speaker of the Maine House

Dawud Ummah, Farmer and Owner of Ummah Gardens

Georgia Zildjian, Castine resident and member of Castine’s Island Name Change Committee

Place Justice Consultants

Erika Arthur, Atlantic Black Box

Meadow Dibble, Atlantic Black Box

Olivia Eckert, Graduate student research assistant, USM

Additional Contributors

Vana Carmona, Researcher of Maine’s Black history

Florence Edwards, Freelance media producer, Facilitator

Jill Williams, Transitional Justice consultant